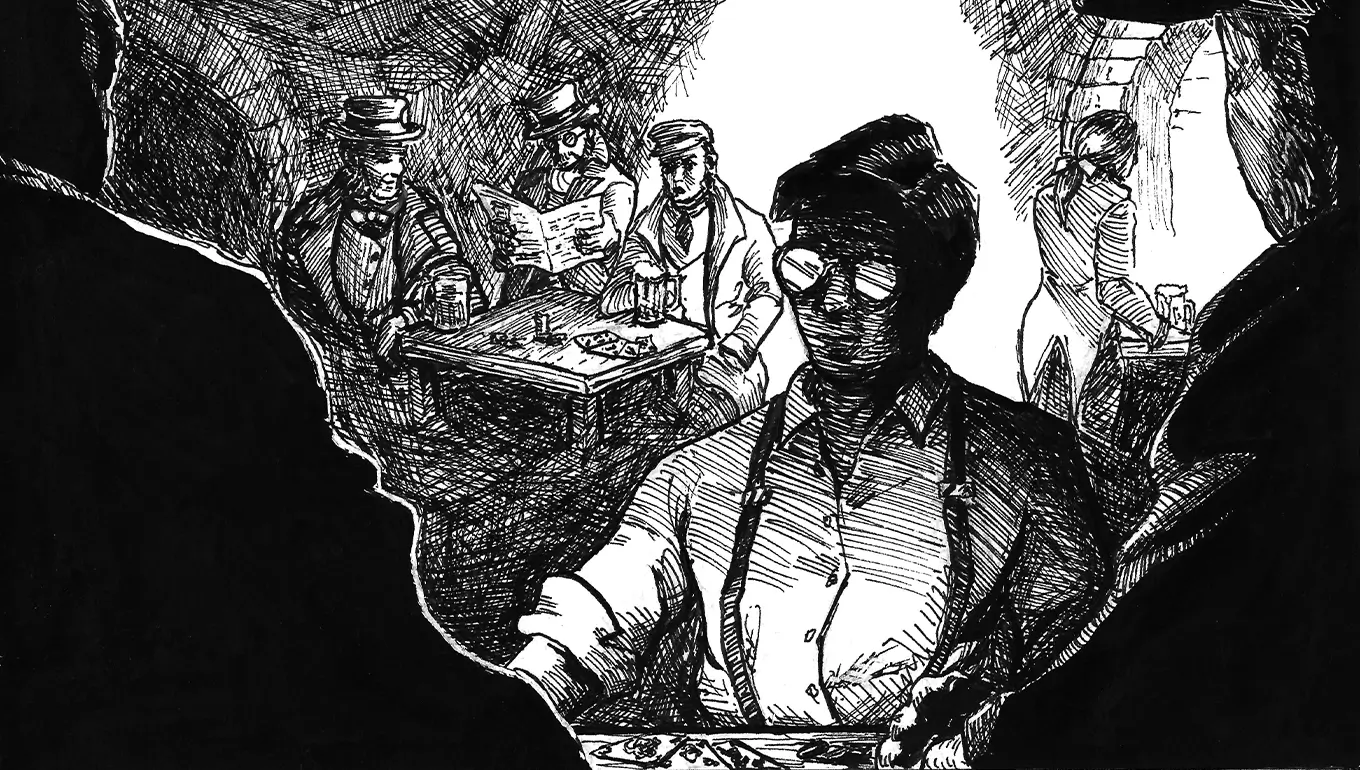

My breaths are echoed by something outside of my own body, but at a quarter to four a.m. there’s nothing, just the snow. I’m watching it sizzle against the tip of my cigarette like hot whispers on a cold winter’s night. Beyond this, the words Paris, 1959 shine in the storm clouds, a classic titles sequence. The score is Bernard Herrmann.

The reviews will be stellar.

I watch the darkness gush through Paris as floodwater does when poured through a miniature town. It splashes thick and nebulous across the brick buildings and lamp posts, strangling their meagre yellow lights. I’ve grown to enjoy this. The all-engulfing darkness. The quiet. I continue to chew on the end of my cigarette, bitter and wet.

There’s something about this city at night and you can’t quite capture it in a cartoon strip in the Canard. The monochrome palette, the repetitive blizzard winds, over and over and over, the drunkards moaning on sidewalks and the leftover music tiptoeing out dead-hour establishments. How to spin a feeling into something tangible? It’s the snow, it’s the fumes, it’s the booze stuck against the sidewalk—well, it’s booze or vomit.

I take a drag of my cigarette and feel the city suck in a breath too.

Yellow headlights catch me as I exhale smoke into the air, dropping the cigarette to the tips of my fingers and letting it dangle by my side. Staring through the yellow haze, I can vaguely make out the face of the car’s sole occupant, a middle-aged man with a clean shave and large red ears. If you asked me, I’d imagine his ears are red because of the weather and not because of some disease of the skin, but who can be sure. This is the fifties, isn’t it, and there’s a lot to be shared around in times like these.

The man isn’t looking at me because he’s peering around at the parking signs, all bent like they’re puking out the snow. You can’t make out a single thing they say, but who’s checking where cars are parked at four a.m. amidst a storm like this?

The car engine goes silent, the headlights vanish in a gasp, and the door clicks open. I shiver as the city gives out a tremble that sounds like brass.

The city freezes frame and the words Nicolas Fontaine flash against the skyline, like the beginning of a Hitchcockian thriller. There’s smoke in the air, gone morbidly rigid; and a woman’s silhouette through her frosted window, fingers gripping the curtain, watching the car, watching me. I look up and she disappears behind a curtsy of fabric.

The large man exits his vehicle, one stocky leg kicking out with theatrics, and then the other. He wears black business pants and glossy shoes, and his suit jacket is congruously black and professional. From the darkness he withdraws a satin hat and slaps it on his horribly-balding head. Then the car door swings shut, scraping the snow-covered footpath with the sound smokers make when they snore.

The Fat Man.

This is all I can glean from him as he locks his car door with a jangle of keys, then walks underneath the streetlamp beside mine, throwing his swollen hands into his pockets. The only thing that marks him as anything besides ordinary is the simple fact he’s out so early and he’s here in front of me. I continue to watch him as I let the cigarette sail from my fingertips and land in the snow, the burning end face-up like an industrial tower pissing smoke.

“Good night,” says the fat man.

His voice alarms me. Baritone and sleepy, it’s as if you crossed the singer Distel, and Constantine from the Lemmy Caution films, rolling out of bed. I gaze at the frost vapour oozing out of the fat man’s fat lips, and suddenly I’m struck with the urge to draw him. He is not a particularly short man but his voluminous suit jacket gives the illusion of stout legs. His top hat speckled with frost provides comical height. My above-average olfactory glands can’t smell anything besides Paris, but I’d imagine his hat carries the stench of dirty backseats.

The fat man’s eyes lift, peering at me ponderously.

“What,” I ask in an unpunctuated tone.

The winds howl in response and the fat man clutches the brim of his hat.

“I said good night,” the fat man repeats. He walks closer with his hands outlined through his pockets, disappearing in the dimness between the two streetlamps, then reappearing in the ambit of mine. He has good skin for a fat man, clean and unblemished.

Finally, he stops. “What did ya think of the show, then?”

The lamp we’re standing under burns out, and then flickers back on again, suddenly accentuating the frost that’s gathering on the fat man’s bushy brows.

Now that he mentions it, I don’t remember much about the show, but my fingers scour my coat pocket instinctively and brush up against a cold ticket stub, which is flimsy and small.

“You got a problem hearing me, boy? Eh? The show’s what I’m talking about, the one down at the theatre just two blocks out. You were there, weren’t ya? Now no use lyin’ about things yet.”

It’s hard to notice a city during the day, when the streets run hot with car fumes and choking exhausts and thrumming engines, but on nights such as this one, an ordinary night in February 1959, even despite the blizzard, you notice it.

For example, the city snickers.

“Have you been following me,” I say.

The fat man glides closer still, his head moving through his most recent gasp of frost. Our close proximity exposes his lack of any substantial height and I find myself almost face-to-face with his top hat. He steps up onto the tips of his toes and says, “Not following you. Just paying attention.”

He looks at me as if that is any reasonable response.

“How do you know who I am,” I say to him.

“I asked at the laundromat,” says the fat man.

“I don’t work down there anymore.”

“Takes more than a resignation to make a person disappear.”

There’s a sudden cramp in my chest, the kind that conjures the thought, I couldn’t be having a heart attack, I’m only twenty-five, and yet the thought passes my head nonetheless. Did I lose consciousness sometime during the night? It would explain why I can’t remember the show, for one.

My hands are riffling my coat for another cigarette. It finally appears in my right hand, lighter in my left. Snap. Hiss. Sizzle. There’s a brief spark of amber. Smoke belly-dances in front of my face as I light the cigarette.

I focus on the fat man, who makes a sound between a cough and a chortle, like a man choking on a really good burger. He’s staring back at me through a sheet of falling snow. If you listened now, you’d hear the scuff of tires on frost-slick roads, of a dog barking across the street, then abruptly stop, as if sensing something in the air had changed.

“Where are my manners, then?” says the fat man in his dulcet voice. “I’m a representative from a corporation currently testing a new kind of drug. We’re looking for participants in a brief trial and your name came up as a potential candidate. Have you ever signed up for anything like this? Been asked, ya lookin’ for a way to earn quick money? That’s probably how we found you in the first place.” A slip of paper crinkles against my fingertips. I clutch it involuntarily. I’m staring over the fat man’s shoulder down the deserted sidewalk, where one of the streetlamps is turning on and off like morse code. I can feel the fat man’s warm breaths reach my neck.

He keeps his voice low and baritone. “I’ve slipped a piece of paper into your hand. On this piece of paper is a number, and if you dial that number you will speak to a man who sounds like a woman but I assure you, he is not a woman, that’s just his voice. This man will put you into contact with another man, and this man will ask you a question, and if you answer this question correctly, you’ll wake up the next morning to find one hundred fifty francs in your bank account.” He shrinks down to his usual, below-average height and looks at me.

“What do you want with a failed cartoonist,” I ask him.

“As the lottery chooses its winner,” the fat man says, “Moscati Research has chosen you.” Despite this, I sense things aren’t so straightforward, and this is no simple lottery.

“Moscati Research. What the hell is that.”

“Moscati Research Laboratories is one of the pioneering forces in scientific development in the twentieth century,” says the fat man. “I have slipped you a piece of paper with a number on it. Once you speak to the man on the other end, you will learn more.”

I remain silent. I don’t recall ever putting my name down for something like this, but all things considered, I don’t trust my memory so much tonight. All I can think of is that I used to pop one every now and then, but then again, how would the fat man know this; and besides, it’s not been for some time. There’s no other reason why I’m being approached except that it’s a con, and it certainly sounds like one. But the look the fat man gives me suggests he’s not playing around, and why did he come looking for me at the laundromat.

The snowing winds suddenly change direction, like a man walking through a grocery store he has never been in before. I become aware of the warmth that a human body gives when its standing nearby another, but at the same time goose bumps spring up on my arms. I think about the fat man’s words, and about the piece of paper enclosed within my cold fingers. There’s not enough space between us for any snow to fall.

“What was the show,” I find myself asking.

The fat man smiles without teeth. I search his eyes for some sign of anything, but it’s like staring into a puddle of trodden-over mud. “Marcel Aymé’s A View from the Bridge,” he says matter-of-factly, frost flying from his mouth. “You ever thought about going to America, Nicolas?”

“Wait a minute, how do you know my name.”

“I told you, I asked at the laundromat where you no longer work, but like I also said, it’s not so easy to disappear completely.”

“Oh.”

The fat man makes a hmph noise, but it could just be a bit of food stuck in his throat, rather than much consideration for anything in particular. “I’ve heard it’s nice over there. America. They have all the good movies, don’t they.”

I have no answer to this. So, without another word, the fat man turns and leaves. All that’s left is the spitting of snow through the space where he had been.

I shiver, clutching the piece of paper and thinking about A View from the Bridge, not that I can remember much from it, pieces of the night censored and forgotten.

The fat man inserts a key into his car door, then climbs in and turns on the ignition. Headlights drench me in hot mustard and I squint, lifting a hand to shield my eyes. Slowly, the car rolls forward until it’s side-by-side with me.

The window rolls down clumsily.

“It’s just a bit old-fashioned isn’t it, the theatre,” the fat man says, directly quoting something I wrote for the Canard maybe three months or so ago. His eyes look askance but his smile stays where it is. He’s lit a cigarette and he perches it on the edge of his mouth. “I liked your cartoons, Nicolas. Very progressive.” He looks back at me—

“Now how the hell’d you end up gettin’ like this?”

I stare at the fat man until the tinted window chomps him up. Wheels screech in the snow and the car disappears up the road, and I’m thinking about the show that I can’t remember, and I’m thinking about what the fat man has told me.

For the first time tonight, I lift the piece of paper in my hand. The left edge is crone’s teeth jagged, like torn from a lined notebook. The phone number has been written in blue pen, obtrusively smudged from the snow. As my phone line was recently disconnected, I don’t currently have access to one directly, but there’s a booth about twenty metres down the road. I glance at it now, covered in frost.

I look back down at the phone number scribbled in blue. By all accounts, ordinary. According to the fat man, if I dial this number there will be a man who sounds like a woman, and then there will be another man who asks me a question. I wonder what sort of question he will ask me.

But if I answer correctly, they’ll pay me one hundred fifty francs, which, times as they are, is decent money. Far more than a few days’ work at the laundromat.

A strange sense of unjudgmental calm comes over me, and I throw the piece of paper onto the ground. Like rats that are hungry, the snow opens up its maws and engulfs it. I kick it with my boot to be sure, and sure enough it’s gone. The cigarette I left there, still sizzling with faint amber, also vanishes under the ravenous snowbank.

At last, with hands in my trouser pockets, I walk away.

In a band room deep down in the catacombs of Paris, one February night in 1959, or a morning, if you have some place to be, a trumpet vomits notes into the city air, and the rest of the band splashes around in it, turning it into music.

I look up as white text dissolves into the air.

It’s the title of a film, superimposed over the darkened sky, untouched by the frost and the streetlamps. Synthetic white text, the font simplistic, Clarendon or Aldine.

Reflections of Fontaine is what it says.